A fundamental reform of the international monetary system has long been overdue. Its necessity and urgency are further highlighted today by the imminent threat to the once mighty U.S. dollar."

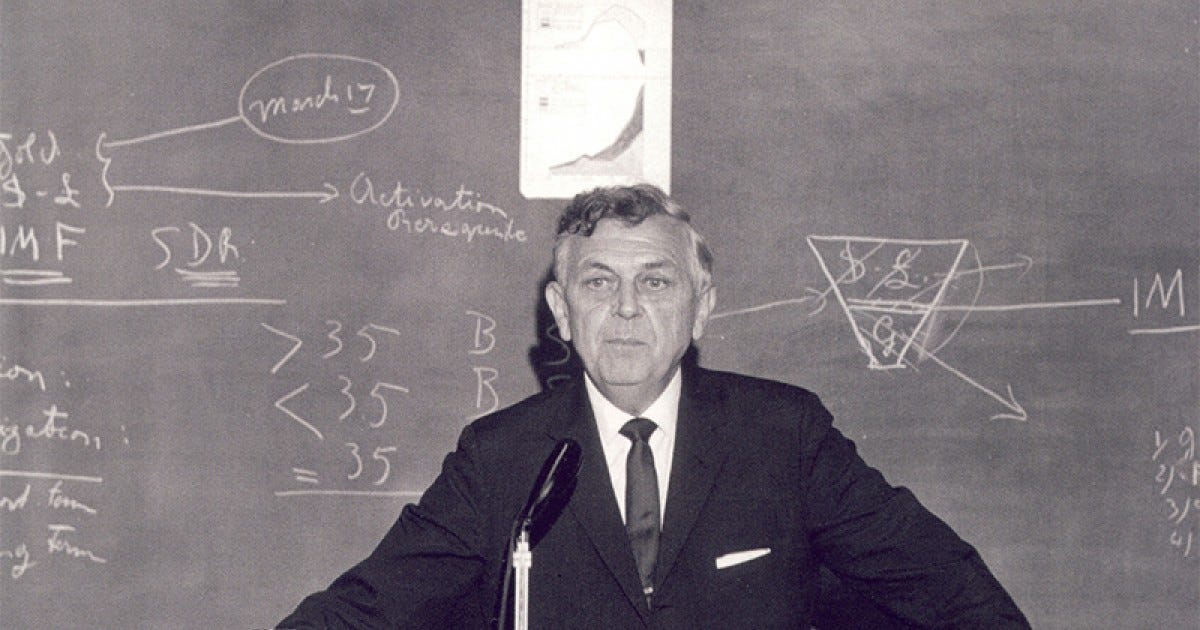

Robert Triffin

November 1960

Introduction

As we live daily lives, very few are aware of the tendrils of the Eurodollar Leviathan which have surreptitiously woven themselves into the fabric of our existence, exerting a profound influence that extends far beyond the realm of finance. In my analysis of the intricate financial plumbing of the Eurodollar system, I want to embark on a journey guided by Aristotle's theory of deduction, by inviting you to unravel the layers of complexity and unveil the underlying principles and explain how this unknown system affects every aspect of our daily lives.

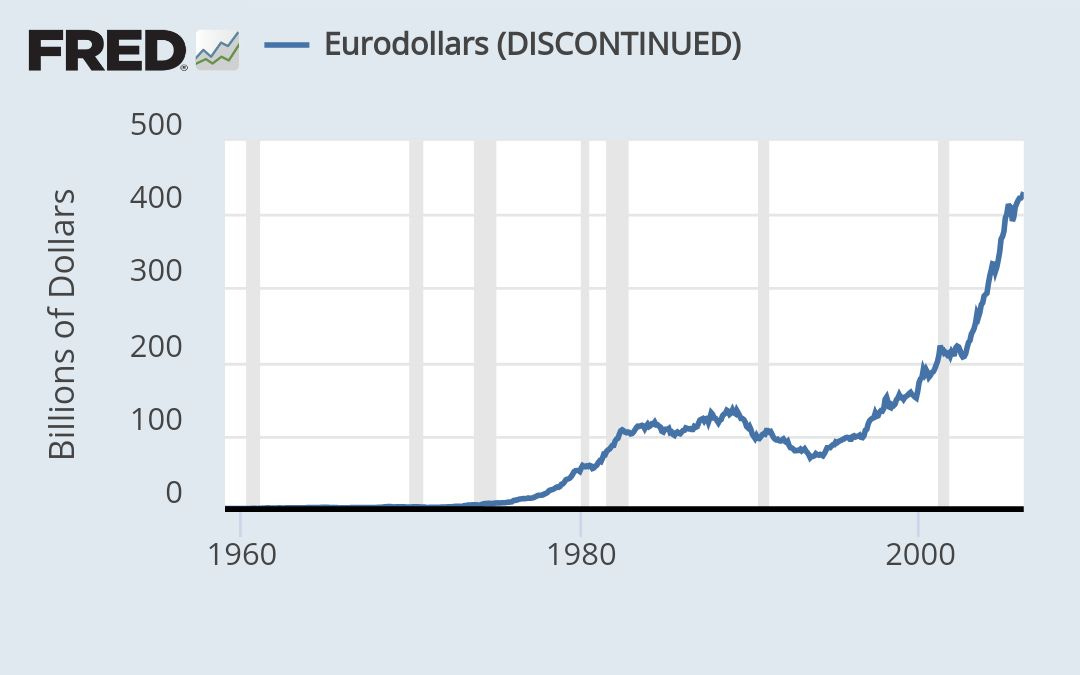

Chart from FRB

Originating as a mechanism post-World War II to breathe life into a war-torn Europe through much-needed financial support. The Eurodollar market has since metamorphosed into a colossal financial entity, where today trillions of dollars is traded everyday. Where the US dollar liabilities, highlighted in Blue in the on the left above, are used a collateral, for the unregulated offshore banking system known as the Eurodollar system.

At its core, the Eurodollar system operates on a foundation built upon dollar based collateral such as US Treasuries, as highlighted in the chart above, serves as the bedrock from which a labyrinth of debt emerges. The delicate balance within this system teeters on the precarious fulcrum of perceived risk associated with the dollar based collateral in circulation. As the scales fluctuate, so too does the ebb and flow of liquidity, with diminishing risk fueling a surge in debt creation while escalating risk triggers a rapid evaporation of available liquidity, as witnessed during the GlobalFinancialCrisis (GFC).

Central to the functionality of this unregulated behemoth is the uninterrupted flow of dollars, a lifeblood that flows through most financial transactions within this elaborate ecosystem. As we dissect the ramifications of this system on the tapestry of our lives, a sobering realisation emerges, I want to explain how and why, this has created endless budgets deficits and the destruction of US and EU manufacturing, manifested from the belief that this Eurodollar system must be saved at all costs.

While my analysis may not be flawless, it is rooted in a commitment to impartiality and transparency. Embracing Descartes' theory of doubt as our guiding principle, I want to navigate this complex terrain in pursuit of shared enlightenment and collective knowledge. It is through this lens of inquiry and introspection that I seek to unravel the enigma of the Eurodollar system and illuminate its far-reaching impact on the intricate web of our interconnected world.

Understand the current Eurodollar System

In 1958, the Bretton Woods system became fully functional as currencies became convertible. The creation of the eurodollar system and the holding of Eurodollar deposits by Central Banks is represented by the dotted blue in the cart above. Countries settled international balances in dollars, and US dollars were convertible to gold at a fixed exchange rate of $35 an ounce. In the euro-dollar system, U.S. dollars are held in accounts outside the United States, primarily in European banks. But a point we need you to understand, was that before 1971, all Eurodollar, where the liabilities of the US Treasury and back by its Gold reserves. However, as the IMF chart above highlights, it only took four years four dollar liabilities to outstrip total Treasury holding of Gold and 1971, when the first Bretton Woods Gold based system collapsed, central bank holdings of Eurodollar deposits was over five times total Gold reserves. This is a critical point we need to first understand, GoldDollars as it was know at the time, are used for international trade and financial transactions. Where the system allows for the circulation of U.S. dollars beyond U.S. borders, making it a key component of the global financial system. However, each dollar is a US Treasury liquidity, yet, the market is completely unregulated.

The creation of dollars in the euro-dollar system typically involves U.S. dollars being deposited in foreign banks or borrowed from U.S. banks by non-U.S. entities. These dollars can then be used for various purposes, such as trade financing, investments, and currency speculation, not exactly risk free enterprises. The flow of dollars in the euro-dollar system is influenced by factors such as international trade, interest rates, currency exchange rates, and global economic conditions, each of which, given that the liabilities are that of the US Treasury, become counterparty risks to the US Treasury. While the system does play a significant role in facilitating global trade and finance, by providing liquidity in the international financial markets. For example Foreign governments and corporations borrow money in dollars to insure their creditors against foreign exchange risk; 64% of world debt is denominated in dollars.

But we need to understand the counterparty risk taken by private banks should not fall on the feet of any government.

Let's break down the creation and collateralization of debt in the euro-dollar system

1. Creation of Debt:

Non-U.S. entities, such as foreign banks, corporations, and governments, borrow U.S. dollars from U.S. banks or issue dollar-denominated bonds in the international markets.

These borrowed dollars are used for various purposes, such as financing trade, investments, infrastructure projects, and working capital requirements.

The creation of debt in U.S. dollars outside the U.S. contributes to the supply of dollars in the global financial system.

2. Collateralization of Debt:

The Eurodollar system is commonly used by companies and financial institutions, such as hedge funds, in order to receive financing. In the Eurodollar system, U.S. dollar loans and bonds are often collateralized with assets, such as government securities, corporate bonds, real estate, or other financial instruments. From which, banks and corporations use this source of collateral for OTC currency swap, commodity hedging and other financial related activities.

Collateralization (combining multiple loans into one loan product) provides more security for lenders, than single source loans, in case borrowers default on their obligations, as helps mitigate credit risk between multiple lenders in the system. But as it's a fractional Reserve System, while collateralization reduces risk, it does not remove it.

The collateralization of debt is what creates liquidity. Banks use statistical modelling to reduce risk. If other banks have confidence in the modelling and future performance of a given bank, then they will continue lending to one another. However, like during the GFC when risk increases and mistrust manifests, liquidity dries up and the US dollar itself becomes counterparty to the value of the collateral.

3. Impact on Global Supply of Dollars:

The creation and collateralization of debt in the euro-dollar system contribute to the expansion of the global supply of U.S. dollars.

This increased supply of dollars outside the U.S. while helping to meet the growing demand for dollar-denominated assets and facilitates cross-border transactions in international trade and finance. Creates counterparty risks for the U.S. citizen as the value of the dollar needs to match the liquidity needs of the Eurodollar system, rather than the domestic economy, which is the very point Triffin was trying to make.

Foundational theories

The Triffin Dilemma, named after economist Robert Triffin, refers to the conflict of interests that arises when a national currency (like the US dollar) serves as the global reserve currency.

Triffin's theory was that he believed that countries that issue the global reserve currency will increasingly face pressure to export more currency to other countries to satisfy global demand. This in turn will lead to inflationary pressures at home as more currency is put into circulation. On the other hand, if the currency is too strong, it can lead to deflationary pressures and hurt exports. This is due to the increased need for the global reserve currency issuer to supply enough currency to meet international demand can lead to persistent current account deficits. This in his view would result in a build-up of debt and external imbalances, affecting the value of the currency.

“If the United States stopped running balance of payments deficits, the international community would lose its largest source of additions to reserves.” (Turfffin congressional speed 1960)

Dependence on a single global reserve currency can leave other countries vulnerable to disruptions in the issuing country's economy or policies. This can lead to instability not only in global financial markets, but in the internal economy of the host nation, as the value and supply of a currency are fixed to meet the liquidity needs of the Eurodollar system, rather than that of the host nation.

Triffin proposed the creation of new reserve units. These units would not depend on gold or currencies, but would add to the world's total liquidity. Creating such a new reserve would allow the United States to reduce its balance of payments deficits, while still allowing for global economic expansion. The Triffin Dilemma, alines with my personal opinion, in that I believe neither Gold or a fixed currency should influence the value and stability of the global financial system. What Triffin does is highlight the challenges that come with having a single currency play a dominant role in the global financial system. However, we must acknowledge that The financial system is much more fluid today, than even in 1993, when Triffin past away, thus any proposed solution must keep this in mind.

John Maynard Keynes

The original arguments of Triffin were heavily influenced by that of John Maynard Keynes and provide a little bit more context, in that his theories were developed as he witnessed the collapse of the British Pound Sterling, as the single global reserve currency, thus must form part of any analysis.

His theory on the potential challenges of the Bretton Woods system, specifically regarding the role of the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency, can be understood through the concept of the inherent conflict between national and international monetary objectives in a system where a single currency serves as the world's primary reserve asset.

Keynes recognized that for the Bretton Woods system to function smoothly, there needed to be a sufficient supply of the reserve currency (in this case, the U.S. dollar) available to facilitate international trade and finance. However, he also foresaw that if the U.S. continued to be the primary supplier of reserve currency, it would need to run persistent deficits to meet the global demand for dollars. “The Keynes plan envisioned a global central bank called the Clearing Union. The International Clearing Union (ICU), aim was to establish regulation of currency exchange, a role eventually taken by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

This bank would issue a new international currency, the “bancor,” which would be used to settle international imbalances”. The bancor was to have had a fixed exchange rate with national currencies, and would have been used to measure the balance of trade between nations. (FederalReserveHistory.org)

Keynes proposed that each country would receive a limited line of credit that would prevent it from running a balance of payments deficit, but each country would also be discouraged from running surpluses by having to remit excess bancor to the Clearing Union. This global bank whose role would be the clearance of trade between nations, similar to a trade exchange with every country as a member and similar, to the original plan of the Federal Reserve as visioned by Walberg.

The plan reflected both Keynes’s concerns about the global postwar economy, but also his view on a centralised top-down financial system. He believed the United States would experience another depression, causing other countries to run a balance-of-payments deficit and forcing them to choose between domestic stability and exchange rate stability.

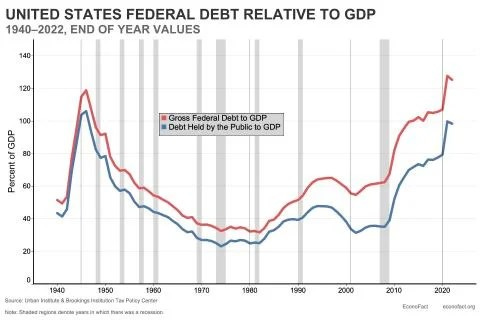

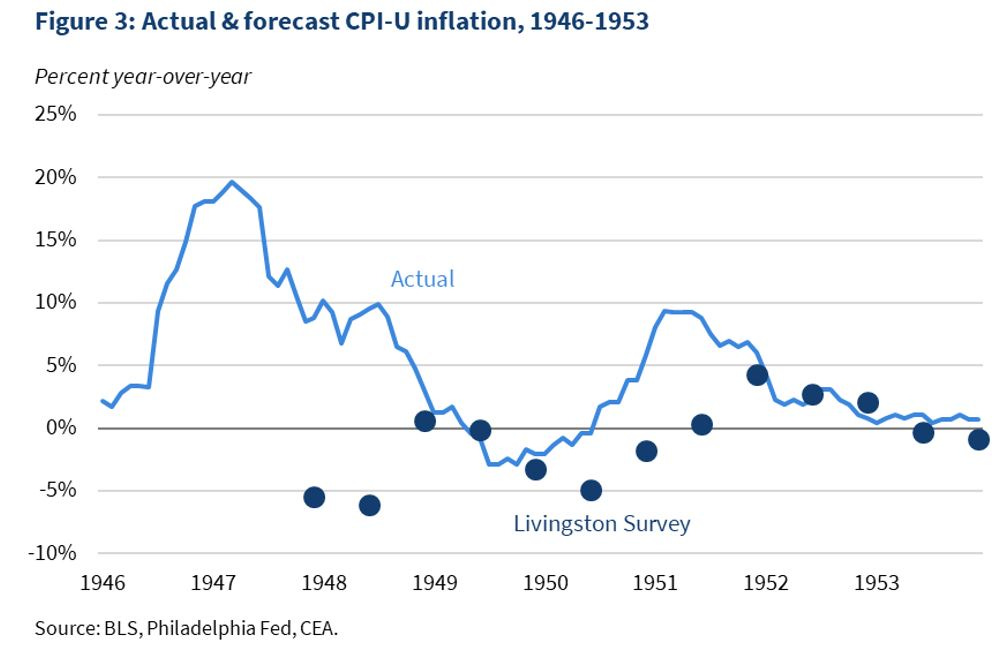

While this was ultimately not the case, this was real danger as U.S. debt to GDP was 117% in 1945. This was on top of the fact, inflation in 1948 was just under 20%, as highlighted in the chart above. Before we move on, I need you to take a second and understand both statistics, in the context of what we are seeing today, where inflation in the four years after COVID-19 is over 25%, the debt to GDP is over 120%, in the U.S. Inorder to understand, first, why the Eurodollar system collapsed in 1971 and to understand the present danger of a future collapse.

Triffin's perspectives became increasingly relevant as the United States encountered growing deficits, particularly exacerbated by the financial strains of the Vietnam War. These mounting deficits ultimately led President Nixon to make the pivotal decision in 1971 to terminate the dollar's convertibility into gold, effectively dismantling the Bretton Woods system that had upheld the post-World War II international monetary order.

Triffin is remembered for having rightly called the break of the gold-dollar link in 1971 in 1959-60. In the event, overall US external liabilities reached the value of the US monetary gold holdings in 1958 (Graph 1, right-hand panel, blue dotted and red solid lines). US liabilities to officials reached that point in 1964 (solid blue and red lines) The point is worth elaboration because the same misapprehension that all dollars are held Stateside afflicts the more recent versions of Triffin discussed below. Four years after Gold and the dollar crisis appeared, the world learned of a stock of $4.45 billion of dollar bank liabilities outside the United States as of September 1963 (BIS, 1964). Then, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) upped its estimate to $6.94 billion (BIS (1965)). Central banks held about half of such offshore dollar deposits (BIS (1966, pp 146-147)), “presumably to obtain higher earnings on these funds” than in the United States (BIS (1964, p 132). What the paper By the BIS is highlighting, is the speed by which, dollars where created outside the US, but most importantly, how little of this was understood by Central Banks.

The collapse of the U.S. credit rating due to the escalating budget deficit arising from financing of the Vietnam War, is the native being given by central banks, but I believe like Jeff Snider, that it was the fact that dollar liabilities outside the US, where five times, told gold reserves, highlight in graph 2 above. The BIS, explained it as, “the gap between global reserve demand and supply was filled by dollars produced by an accumulation of official short-term claims on the United States from the early 1950s. In contemporary terms, the United States was running US balance of payments deficits under official settlements, as it accumulated liabilities to foreign officials without increasing official assets like gold”. (BIS)

This scenario not only undermined the credibility of the U.S. as a stable reserve currency, but also jeopardised the financial plumbing of the Eurodollar system, highlighted by the vivid image, August 1971, when French president Pompidou sent a battleship to New York harbour to remove France's gold from the vault of the New York Federal Reserve Bank and to transport it to the Banque de France in Paris. The Eurodollar system encompasses the intricate mechanisms and institutions that enable the creation, transfer, and circulation of U.S. dollars outside the United States. Illustrating the vulnerabilities of the global financial infrastructure, which utilmantly forced Nixon to default on its Gold obligations.

The breakdown of the Bretton Woods system and the subsequent challenges faced by the U.S. highlighted the fragility of relying solely on one national currency as the linchpin of the international monetary system. Triffin's and Keynes's warnings regarding the risks associated with such a dominant position for a single currency foreshadowed the eventual unravelling of the established global financial architecture. What the U.S. did in response was not reform, but to double down, to use the U.S. military as vehicle to maintain U.S hegemonic power, through the creation of the Petrodollar system.

GFC 2008

In the 40 years after Nixon defaulted on its Gold obligations, the U.S. ensured its hegemonic power, through a combination of military dominance and fiscal spending, which is clearly illustrated in the chart above.

However in 2008, liquidity dried up in the Eurodollar system. As risk in the financial system increased, financial institutions faced a liquidity crunch and concerns over counterparty risk escalated, funding in U.S. dollars became scarce in the offshore markets. This led to a freeze in interbank lending and disrupted the flow of U.S. dollars in the euro-dollar system.

Figure 3 shows how three-month LIBOR started rising with the Lehman failure in September and continued to rise unevenly into October, despite the stabilisation of money market funds. Expected overnight rates over the next three months as captured in overnight index swaps began to decline in mid-September, and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) ratified these expectations by lowering its target fed funds rate by 50 basis points on October 8th.

In response to the liquidity crisis, central banks in the U.S. and the EU implemented various policy measures to ensure efficient liquidity in the euro-dollar system:

1. Federal Reserve (US):

The Federal Reserve injects liquidity into the financial system to stabilise markets and support banking institutions.

The Fed expanded its swap lines with other major central banks, including the European Central Bank (ECB), to provide U.S. dollar liquidity to foreign financial institutions facing funding strains.

Through various programs such as the Term Auction Facility (TAF) and the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF), the Fed provides emergency funding to address liquidity shortages in the financial system.

2. European Central Bank (EU):

The ECB also implemented measures to address the liquidity crunch in the euro-dollar system and support financial stability in the euro area.

The ECB provided euro liquidity to European banks through its various liquidity operations, including Long-Term Refinancing Operations (LTROs) and Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs).

The ECB participated in coordinated actions with the Fed and other central banks to ensure the availability of U.S. dollar funding in the offshore markets.

The chart above from the great depression shows how the central banks them selves restrictef the supply of credit to the system (highlighted by the gold line). Understanding this Central Banks thought that by providing liquidity support and enhancing coordination between central banks, these policy responses would ease funding pressures, restore confidence in the financial system, and ensure the efficient functioning of the euro-dollar market. While these actions helped prevent a further escalation of the liquidity crisis, from this point on words not only did this remove the independence of central banks, with regards monetary policy, understanding this, the market removed the counterparty risk from the banks themselves to the state..

Collaboration of Central banks

The Collaboration among central banks and regulatory authorities, was clearly exposed to the markets during the EU debt crisis, between 2010 and 2014, which created untold fragmentation and nearly broke up the monetary Union.

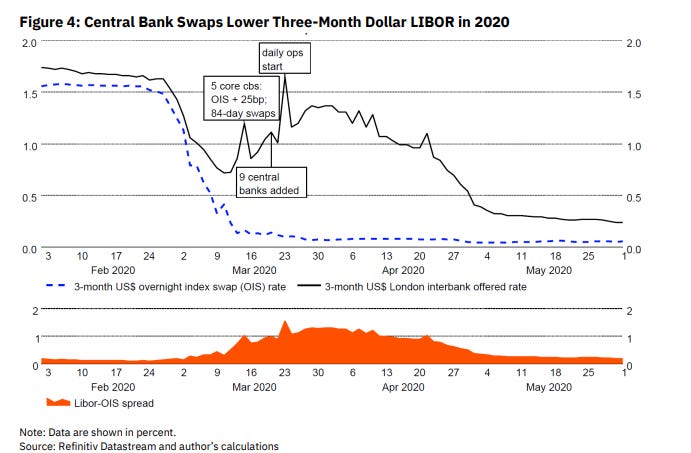

Swiftly, the Fed acted to keep the transmission of its interest rate policy to the real economy from breaking down. The very next day, the Fed eased its interest rate on central bank swaps from OIS+50 basis points to OIS+25 basis points for five core central banks with standing swaps; it also offered 84-day swaps. LIBOR fell but then began to rise again, and the Fed extended the swaps to the other nine central banks on March 19. 13 The start of daily swap operations on March 23 marked the local maximum of LIBOR, which fell to within 25 basis points of OIS by early May. With these swift moves, Fed credit extended to central banks through swaps rose much more sharply in 2020 than in 2008 but peaked at a lower level at less than $500 billion. Much faster than in 2008, the Fed brought down the premium on borrowed dollars in the eurodollar market and in the FX swap market (Choi et al. 2022).

The EU debt crisis showcased the collaboration among central banks and regulatory authorities not only within the EU but also on a global scale. The crisis highlighted the interconnected nature of financial systems and the need for coordinated efforts to address the challenges arising from sovereign debt issues and economic instability. But this intervention only made things worse in the long run. As citizens of Germany and France, refused to underwrite the perceived fiscal irresponsibility of national government’s, refused to socialise the debts of other nations like Greece and Portugal.

The often overlooked integration of US monetary transmission and the eurodollar market impelled the Fed toward an all-out effort as international lender of last resort. The short-term dollar benchmark in the futures market tipped from Treasury bills or US certificates of deposit in 1984, the year of the run on Continental Illinois. In parallel, banks shifted the pricing of their US corporate loans from prime or domestic certificates of deposit to LIBOR. This shift reflected and facilitated the increasing share of foreign banks in the US commercial and industrial loan market in the 1980s.10 Twenty years later, the rising share of foreign banks as packagers and holders of US mortgages favoured the internationalisation of the pricing of US adjustable-rate mortgages (Morgenson 2012).

However the decline in the EU didn't happen overnight. EU countries grappling with the debt crisis faced multifaceted challenges exasperated by years of deindustrialization. The decline of manufacturing sectors not only impacted domestic economies but also influenced trade dynamics within the region and with other global markets. The trade imbalances exacerbated by the crisis added complexity to the economic landscape, as countries struggled to address deficits and surpluses while managing structural adjustments to stabilise their financial positions.

This was highlighted in a DSGE simulations which suggest that high-debt economies:

can lose more output in a crisis,

may spend more time at the zero-lower bound.

are more heavily affected by spillover effects

face a crowding out of private debt in the short and long run.

have less scope for counter-cyclical fiscal policy

are adversely affected in terms of potential (long-term) output, with a significant impairment in case of large sovereign risk premia reaction and use of most distortionary type of taxation to finance the additional debt burden in the future.

By understanding the complexities of the Eurodollar system within the context of the EU debt crisis, we begin to release functionality of the euro-dollar system that encountered significant pressures. Trade imbalances and uncertainty surrounding sovereign debt levels impacted the demand and supply of U.S. dollars, affecting liquidity conditions and financial stability, by creating imposed inflation outside the U.S. at a time when the global economy was already under stress. The crisis prompted the Federal Reserve to navigate through intricate liquidity challenges, by ensuring the flow of U.S. dollars in the global market, influencing exchange rates, capital flows, by an unprecedented level of quantitative easing (QE). The result of which, 15 years on, is that we are facing massive economic and political instability. However, we must understand that all this was coordinated at the very top and that the dangers this would create was highlighted well in advance.

A thought experiment on how a global monetary system works

Building on the points discussed, we can deduce a thought experiment on how a global monetary system based on the value of one hegemonic power can erode the economic and social fabric of that society over time, leading to division and instability within the host nation. Let's outline this thought experiment incorporating historical examples:

1 The foundation

A nation establishes itself as the hegemonic power in the global monetary system, leading to economic dominance, trade advantages, and prosperity fueled by the circulation of its currency as the global standard of value.

2. Over time

The reliance on a single hegemonic currency creates disparities within the host nation, where access to capital and wealth accumulation becomes concentrated in the hands of a few elites who benefit from the dominant currency's status. This divide between the capital-rich and labour-dependent segments of society widens, leading to economic inequalities, social unrest, and political tensions as marginalised groups struggle to achieve economic mobility and financial security.

3. Historical Examples

French Revolution and the disparities in wealth and privilege between the aristocracy and the common people in France, exacerbated by economic hardships and financial mismanagement, fueled the social unrest that culminated in the French Revolution of 1789.

Decline of the Roman Empire and the debasement of the Roman currency, economic stagnation, and social inequality contributed to the weakening of the Roman Empire, leading to its eventual decline and fragmentation.

The interconnectedness of global financial systems, combined with the dominance of the pound sterling as the world's reserve currency, played a role in the economic instability and social upheaval of the 1930s, including the Great Depression and the rise of totalitarian regimes.

As the hegemonic power loses its grip on global monetary dominance, the economic and social fissures within the host nation become more pronounced, impacting stability, social cohesion, and political governance. The diminishing hegemonic power struggles to maintain economic supremacy and faces challenges in addressing internal disparities, leading to crises, revolutions, and societal transformations as power dynamics shift and new monetary systems emerge.

The historical examples of the French Revolution, the decline of the Roman Empire, and the chaos of the 1930s as the British Pound collapsed, demonstrate how a global monetary system centred around one hegemonic power can contribute to economic and social divisions within the host nation over time, ultimately affecting the fabric of society and the stability of the monetary order. But we have to remember, this doesn't happen in a vacuum, nor does it happen overnight.

Jimmy Goldsmith's warning to the world

In the 1990s, Jimmy Goldsmith, British entrepreneur and politician, warned about the potential negative impacts of globalisation on US and EU societies. Goldsmith articulated concerns about how globalisation, characterised by free trade, capital mobility, and market liberalisation, could lead to adverse consequences for economies, industries, and communities. His theories have, to a large extent, resonated with certain developments in the decades following his warnings.

Goldsmith's warnings about globalisation highlighted the potential erosion of industrial sectors and job loss in traditional manufacturing hubs. Detroit, once a thriving industrial centre known for its automobile manufacturing, has experienced significant decline due to factors such as globalisation, automation, and competition from overseas manufacturers. The city's population decline, high unemployment rates, and loss of manufacturing jobs have been attributed to the impact of globalisation on industries that were once the backbone of the economy.

Similar trends can be observed in cities like Baltimore and Oakland, which have faced economic challenges and social issues linked to globalisation and deindustrialization. Baltimore, a port city with a history of steel production and shipping, has seen job losses in manufacturing and related industries, contributing to urban blight, poverty, and social inequality. Oakland, known for its port and manufacturing activities, has also grappled with economic restructuring, declining industrial sectors, and disparities in income and opportunities.

Goldsmith's warnings about the shifts in economic structure, job markets, and social dynamics don't underscore the complex impacts of globalisation on national economies, but underscore the political choice between ensuring the financial stability of the Eurodollar system, over the economic stability of the home nations. The interview Jimmy Goldsmith did with Charlie Rose in 1990, is a must watch, to understand the economic landscapes and the need for policies that address the social and economic consequences of globalisation and the need for reform of the global financial and monetary system

The gradual erosion of a hegemonic currency

The gradual erosion of a currency's value, such as U.S. dollar highlights in the chart above, have long-term implications for the hegemonic power of a nation. We must understand that it's a gradual process. Over time, increasing the budget deficit creates inflationary pressures, which lead to a relative loss of purchasing power, which over time creates political and social inequality and instability.

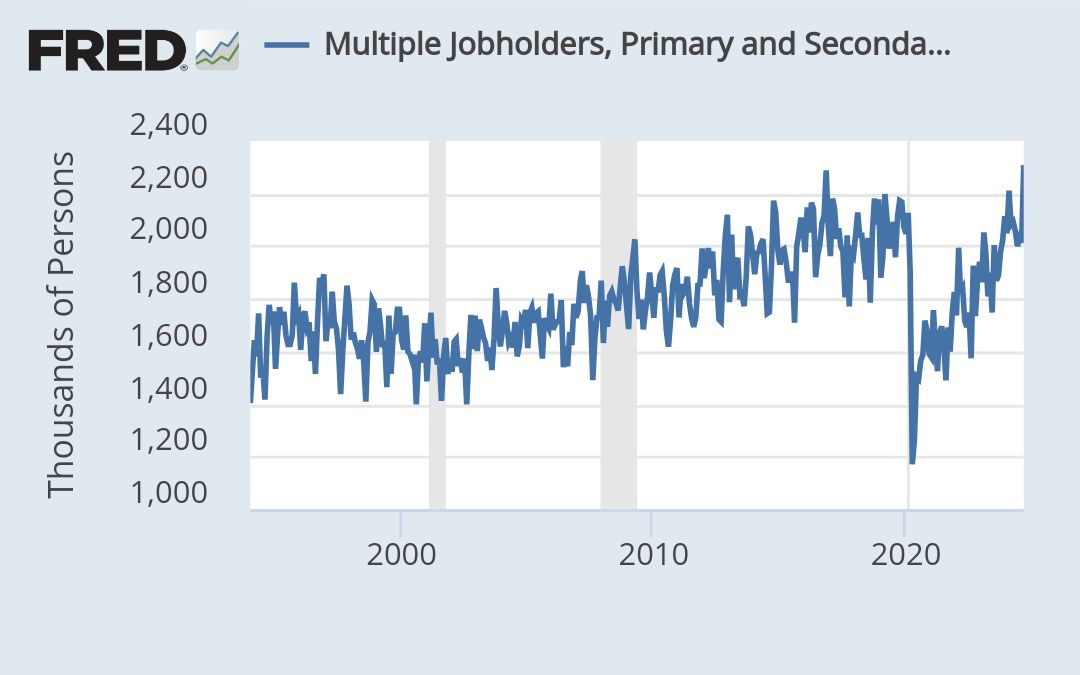

Inflation, as a result of weakening currency, reduces the value of savings, diminishes purchasing power, and increases the cost of living for citizens. This creates economic hardships and dampens incentives for innovation and entrepreneurship, as citizens. As citizens have to take on multiple jobs, are they increase the level of overtime to maintain their standard of living. This can be highlighted in the chart below, were without the exception of COVID-19, from 2008, there as been a steady increase in the number of multiple job holders.

Over the last 3000 years, countries like England, France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece have each experienced periods of global dominance and influence, driven by factors such as military power, economic prosperity, and cultural achievements. However, the fortunes of these nations have fluctuated over time, with shifts in economic strength, geopolitical dynamics, and currency stability influencing their positions on the global stage. Today, while these countries boast rich histories, their global dominance has waned compared to previous eras.

The gradual erosion of a nation's economic power, symbolised by currency devaluation, inflation, and diminished innovation, mirrors a slow accumulation of setbacks akin to the concept of "death by a thousand cuts." This prolonged decline, as illustrated by historical examples of former dominant powers, may not result in immediate catastrophe but can lead to a waning hegemony, with far-reaching consequences such as economic deterioration, social unrest, and diminished global influence.

I hope by having a greater understanding of The Triffin Dilemma and Keynes's theory on the risks associated with a single global reserve currency, we better understand the increasing workload and financial strain on individuals due to economic pressures taking on added significance, caused by the erosion of the global reserve currency. The erosion of a nation's currency value, exacerbated by a singular global reserve currency system, creates complexities that hinder innovation and progress. Manifested, in high levels of personal debt restrict financial flexibility, limiting individuals' capacity to save, invest, or engage in creative endeavours that spur personal and societal growth.

As individuals become ensnared in a cycle of debt and excessive work demands, their cognitive capacities for critical thinking, problem-solving, and innovation are compromised. In a society where time equates to a valuable resource, the erosion of time resulting from economic burdens and financial constraints becomes a critical constraint on creativity, entrepreneurship, and overall advancement. The combined impacts of currency devaluation, personal debt burdens, and relentless work pressures diminish individuals' most precious asset – their time – impeding their ability to envision and contribute to a brighter future for themselves and society at large.

Supply elasticity

To truly understand money, finance and the Eurodollar System, you need to understand the complex interplay of supply elasticity. Imagine the elastic band as a representation of the supply dynamics within the intricate web of global finance, particularly within the Eurodollar system. Initially, as you begin to stretch the band, it displays a robust resistance to breaking, akin to a market with inelastic supply characteristics. This resilience implies that minor fluctuations in price or demand have minimal influence on the quantity supplied, mirroring certain segments of the financial landscape that exhibit limited responsiveness to external shocks.

However, with continued stretching over time, the band undergoes a subtle but significant transformation, gradually losing its once formidable strength. This gradual weakening symbolizes the concept of supply elasticity in economics, highlighting how markets can evolve from inelastic to elastic conditions under sustained pressure.

In the context of the Eurodollar system during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the freezing of interbank lending acted as a powerful stressor on the financial elasticity of the system, akin to the increasing pressure applied to the stretched band. Amidst this turmoil, central banks intervene with the infusion of liquidity through Quantitative Easing (QE) measures to bridge the widening gaps and prevent a catastrophic rupture in the financial fabric.

The act of injecting liquidity can be likened to administering steroids to bolster resilience temporarily, providing a crucial lifeline to a strained system. Yet, as pressures mounted and these temporary measures reached their limits, a point of reckoning emerged, compelling a strategic retreat or recalibration to avoid catastrophic failure.

This pivotal juncture in the economic narrative underscored the intricate balance between short-term remedies and long-term structural implications. The consequences of QE, intended to stabilise the system, unwittingly set off a chain reaction leading to a sovereign debt crisis in Europe, exemplifying the nuanced repercussions of interventions in complex financial ecosystems.

In essence, the thought experiment illuminates the cyclical nature of crises and responses within the financial domain, emphasising the profound interconnectedness and intricacies that define modern markets. Understanding the elasticity of supply within this intricate framework is vital, in understanding the volatile terrain of global finance.

In the context of the thought experiment and the Triffin Dilemma, let's explore how the current surge in fiscal spending and government debt could be likened to the elasticity of an extended band.

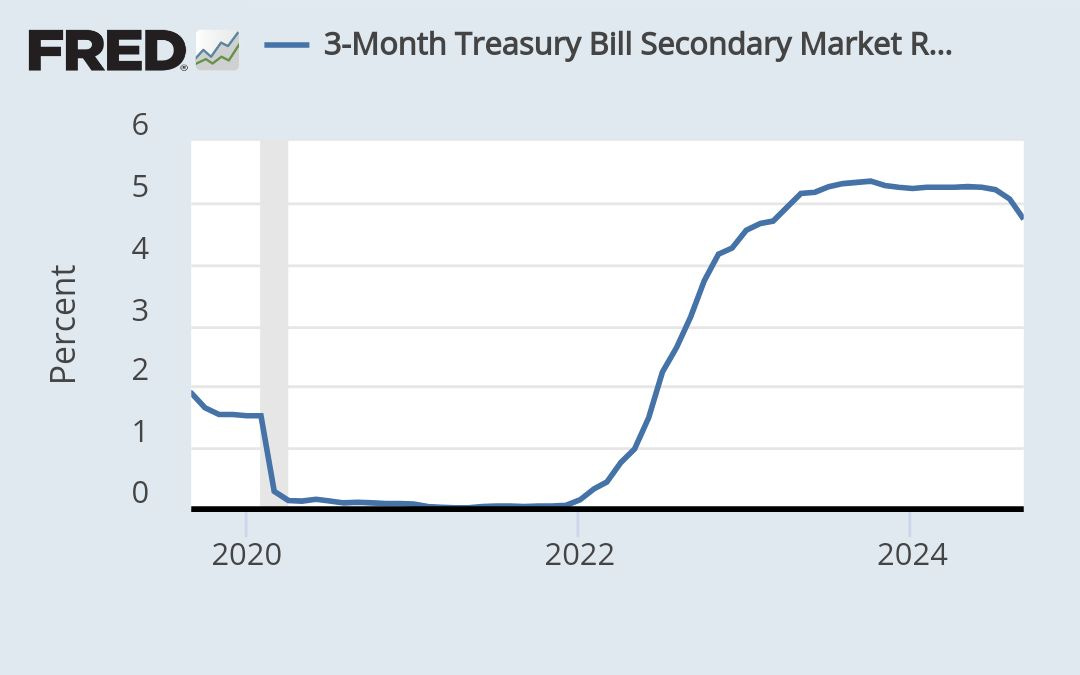

Now, imagine the current explosion of fiscal spending and government debt as the act of further stretching the elastic band in the economic landscape. Just like the band in our analogy, the system initially responds with resilience and apparent strength to accommodate the increasing demands of economic stimulus and debt issuance. As we saw in March, 2022, during the mini banking crisis when Treasury Security Yellen started restructuring how the Treasury finances the country's debt. Where she should large Tranches to long-term debt, replacing it with short-term T-bills, the most secure form of collateral in the financial system.

This allowed the band, representing the economy, to be stretched further to avoid the predicted deflation and unemployment outcomes of the Triffin Dilemma; while the system clearly temporarily absorbed the strain. The extra supply of liquidity shored up collateral values in the short term, creating more liquidity. This allowed for greater elasticity, which in turn gave Yellen the space for what she perceived as necessary fiscal interventions to prevent economic contraction and stabilise employment levels, before the upcoming election cycle.

But like any elastic band, it always breaks, yet never gives you any warning.

Similar to our earlier discussion on supply elasticity, there comes a point where the stretched band must either contract, risking a potential backlash of economic consequences, or face the challenge of being held in an extended state for prolonged periods. This prolonged strain on the system, comparable to the implications of sustained fiscal spending and rising government debt, can introduce fragility and vulnerabilities that may lead to systemic risks, which we can only understand as the known unknowns.

The parallels between the elasticity of the band in our thought experiment and the current economic policies aimed at addressing the Triffin Dilemma highlight the delicate balance between short-term interventions and long-term implications. Just as the band requires careful management to prevent sudden snapback, policymakers navigating the complexities of fiscal spending and debt accumulation must consider the trade-offs between immediate stability and the sustainability of the economic system in the long run.

Understanding the correlation between risk and currency supply

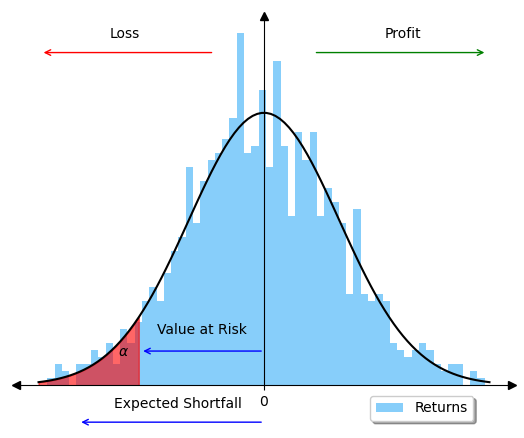

The simplest form of financial modelling to explain is Value at Risk (VaR) and is a widely used measure in finance to assess the potential loss that an investment portfolio or a financial institution may face within a specific time horizon and at a given confidence level. In the context of a bank operating in the Eurodollar market, financial models like VaR are employed to quantify the risk exposure associated with various assets and liabilities, particularly in decentralised finance where efficiency and self-interest play crucial roles.

1. Debt and Risk:

In the Eurodollar system dollar denominated debt, serves as a medium of exchange that provides collateral within the interbank lending system. Which in turn relies on trust and consensus within the market system, of the health of each stakeholders balance sheet and this is done through financial modelling.

Through modelling, individuals gain trust and can engage in various financial activities, such as lending, borrowing, and trading, where the efficient allocation of capital is essential. However, the decentralised nature of these systems introduces risks related to asset valuation, counterparty risk, and market volatility. Thus, when banks have confidence in each other's balance sheet, risk is represented in the blue area in the chart above and when the system is under stress, because banks are exceeding their risk tolerance, represented in the red shaded area.

Banks understand each other's risk and potential VaR ratio, because they are all treading and modelling the same assets.

2. Self-Interest and Efficiency:

A bank operating in the Eurodollar market can use a VaR model to quantify the potential losses it may face due to market movements, currency fluctuations, interest rate changes, and credit defaults. By incorporating factors such as asset correlations, volatility analysis, and stress testing, the bank can assess its risk exposure and make informed decisions to manage and mitigate risks effectively.

Participants in the Eurodollar market act in their self-interest to maximise returns and minimise risks. This pursuit of self-interest can lead to efficient allocation of capital as market forces drive decisions based on individual preferences and risk appetite. Where, when risk is perceived to be low, debt creation increases (represented by the curvature of the black line in the chart above. However, self-interest can also contribute to volatility and liquidity issues, as participants may prioritise their own gains over the stability of the overall system. Where they reduce interbank lending, to the point that when banks risk breaching their own risk tolerance lending and there for liquidity freezes. As shown in the bottom left of the chart above.

3. Collateral Valuation and Risk Mitigation plays a crucial role in mitigating risks associated with lending and borrowing activities. Banks and other financial institutions can use VaR models to assess the value of collateral assets, monitor collateral adequacy, and evaluate the potential impact of market fluctuations on collateral values. By incorporating VaR analysis into their risk management frameworks, banks can enhance their ability to manage credit risks and ensure the stability of their operations in the Eurodollar market. However, when the risk increases and liquidity dries up, it's the Central Banks, especially the Federal Reserve that see themselves as lending of last resort, even though they have no regulatory authority over the activities within the Eurodollar system.

What is the solution?

Self-interested behaviour and game theory play integral roles in the context of the Eurodollar system, particularly in understanding the incentives and interactions among participants in the ecosystem. As can you use the envision of Satoshi Nakamoto's theory of Bitcoin, to create a clear immutable and transparent Eurodollar system? Here is an analysis emphasising self-interested behaviour and game theory:

1. Self-Interested Behaviour in Decentralised Finance:

Self-interested behaviour refers to individuals acting in their own best interest to maximise their gains or minimise their losses. In decentralised finance, participants engage in various activities such as trading, lending, and mining with the goal of achieving their financial objectives. Satoshi Nakamoto's design of Bitcoin incentivizes self-interested behaviour by rewarding miners for securing the network and validating transactions, and by providing users with fast and low-cost transactions.

We need to understand that the Eurodollar system is not a monetary based system, but a ledger based system. Thus we need to create a system, as highlighted by Satoshi Nakamoto, that incentives and rewards good behaviour and reduces the incentives of cheating.

2. Game Theory in Decentralised Finance:

Game theory provides a framework for analysing strategic interactions among rational players in situations where the outcome of one player's decision depends on the decisions of others. In the context of decentralisation and the Eurodollar System, game theory can help understand the dynamics of competition, cooperation, and incentives that shape participants' behaviour in the ecosystem. Participants in decentralised finance engage in strategic interactions based on their self-interest, seeking to maximise their utility given the payoffs and risks involved.

This can only be done through and immutable and transparent clearing system for the Eurodollar system, one the Keynes advocated for from the outset. But rather than a centrally controlled clear system, it needs to be decentralised in a transparent ledger-based system.

Incentive structures are crucial in influencing participants' behaviour and decision-making processes. Satoshi Nakamoto's design of Bitcoin incorporates a reward system for miners and users that aligns with the principles of game theory, encouraging participants to act in ways that benefit the overall network. Nash equilibrium, a concept in game theory where no player has an incentive to change their strategy given the strategies of others, can be observed in decentralised finance when participants collectively pursue their self-interest while maintaining the stability and security of the network.

3. Risk Management and Collective Action:

Self-interested behaviour and game theory also play a role in risk management and collective action within decentralised finance. Participants must balance their individual interests with the broader goals of maintaining a secure and sustainable financial ecosystem. By understanding the incentives and motivations of all participants, decentralised finance can leverage game-theoretic principles to enhance risk management practices, foster collaboration, and promote the long-term viability of the ecosystem.

This needs to be done by removing the dollar as the single source currency as a medium of exchange and allowing the market to determine the medium of exchange.

The collateral should be based solely on the assets being traded. This in turn creates transparency within the system and limits the counterparty risk to the state.

Banks operating in the Eurodollar system, should be wholly owned companies and their operations should be separate to that within the state they are regulated. This again reduces counterparty risk to ordinary bank customers, and enforces banks to do their own due diligence and risk analysis.

Now we can use this concept to imagine a decentralised financial ecosystem where individuals, driven by self-interest and empowered by transparent protocols and smart contracts, engage in a network of peer-to-peer transactions. In this decentralised environment, price discovery operates as a natural phenomenon, guided by open market dynamics and real-time interactions among participants. Unlike the current monetary system dictated by central authorities, DeFi leverages the collective actions of self-interested individuals pursuing optimal outcomes in a competitive landscape. This decentralised structure minimises bureaucratic inefficiencies and potential biases inherent in centralised decision-making processes, promoting greater market efficiency and innovation.

By placing trust in transparent algorithms and decentralised governance models, DeFi offers a more inclusive and accessible platform for financial participation, fostering greater financial autonomy and empowerment among global stakeholders. In this context, the self-interested behaviours of individuals, guided by rational decision-making and market forces, are envisioned to drive more efficient resource allocation, risk management, and value creation within a decentralised financial framework, showcasing the potential benefits of DeFi as a dynamic and responsive monetary policy alternative.

Conclusion

The complexities of the Eurodollar system and the theories of Triffin, Keynes, and Goldsmith, intertwined with historical trajectories and contemporary complexities, converge to illuminate the profound implications of global monetary systems on economic power, social dynamics, and the fate of nations. The cautionary tales shared by these prominent thinkers underscore the delicate balance between dominance and decline, shedding light on the intrinsic vulnerabilities embedded within the fabric of hegemonic currencies and global financial frameworks.

Triffin’s insights into the inherent contradictions of a single global reserve currency, Keynes’s warnings on the risks of economic imbalances and speculative greed, and Goldsmith's concerns about the disruptive impacts of globalisation collectively echo the imperative for nations to navigate the intricate interplay of economic forces with prudence and foresight. Their theories, often forgotten or ignored, serve as guiding beacons, from which I feel a duty to urge policymakers to cultivate a path for decentralisation and healthy competition among nations, rather than living through the current centralised chaos. However, this needs resilience, inclusivity, and innovation in the face of evolving paradigms and challenges in the global economic landscape. Something that is clearly missing in the policies of both political candidates for U.S. president.

We are clearly living through the gradual erosion of hegemonic power of the dollar and the widening economic disparities reverberate through society, manifesting in strained innovation, diminished investment opportunities, and social discord. The historical tapestry of rise and fall elucidates the impermanence of dominance and underscores the imperative for adaptability, collaboration, and equitable progress in sustaining enduring influence and prosperity on a global scale.

As nations seek to establish sustainable foundations for economic resilience and enduring influence, the transition towards a global monetary system anchored on decentralised, asset-backed principles emerges as a transformative pathway. By leveraging blockchain technology to foster transparent, immutable, and efficient financial transactions, nations can unlock new levels of trust, security, and innovation in the global financial ecosystem.

The integration of quality, real-world assets with intrinsic economic and monetary value as collateral underpins the strength and integrity of this decentralised system. Tokenization further enhances liquidity, transparency, and adaptability, creating a dynamic marketplace that aligns with the principles of economic stability, inclusivity, and long-term prosperity advocated by Triffin, Keynes, and Goldsmith.

By embracing a holistic approach to designing a global financial infrastructure rooted in decentralised, asset-based principles, nations can forge a resilient and adaptive system that mitigates risks, fosters sustainable growth, and safeguards against systemic shocks. This evolution towards a decentralised, transparent, and inclusive monetary system echoes the wisdom of historical lessons and theorizations, offering a pathway towards a more equitable and efficient global economy resilient in the face of the transformative forces shaping our world today and into the future.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/other-publications/ire/annex/pdf/ecb.ire202406_annex.en.pdf